According to a new study, the rings and tilt that the planet Saturn is best known for could have been the result of an ancient, missing moon that had a “grazing encounter” by smashing a moon to bits, hence forming its rings.

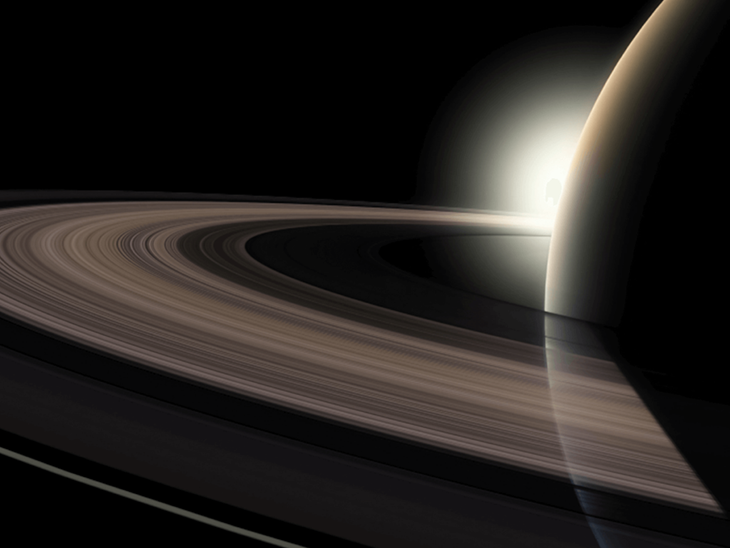

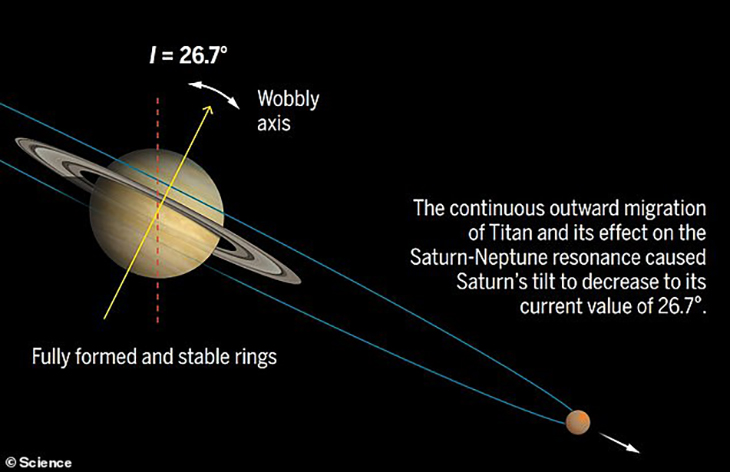

The rings of Saturn, which swirl about the planet’s equator, is what the planet is best down for. Moreover, it’s what makes it obvious that the planet spins on a tile. This giant planet rotates at a 26.7-degree angle in relation to the plane in which it orbits the earth’s biggest energy source, the sun. Astronomers have suspected for many years that Saturn’s signature tilt is from gravitational interaction with Neptune, its neighboring planet, since its tilt is much like that of a spinning top that moves at the same rate as the Neptune’s orbit.

However, a new modeling study from astronomers out of MIT and other school have figured out that, although these two planets were once at sync, lately, Saturn has since escaped the pull of its neighbor, Neptune. But they wonder, what could have caused this planetary realignment? According to the scientists, one of their meticulously tested hypotheses is a one of Saturn’s missing moons.

A study, which came out in the Science journal, shares how the team suggest how Saturn – which has 83 moons today – once had one more moon, which was an extra satellite named Chrysalis. Alongside its siblings, the research team suggests that Chrysalis once orbited Saturn for several billion years, tugging and pulling the planet in a way that kept is tilt, otherwise known as obliquity, in symmetry with Neptune.

Then around 160 million years ago, the researchers claim that Chrysalis became unstable and came too close to the planet, which resulted in a grazing encounter that pulled the satellite apart. With the loss of this moon, it was also enough to pull Saturn away from Neptune, leaving it with its present-day tilt.

Moreover, the scientists believe that although most of the shattered body of Chrysalis made impact with Saturn, a portion of its fragments may have remained suspended in orbit, then eventually breaking down into smally icy pieces, forming the planet’s beloved rings.

As for the missing satellite, the scientists say that they could explain two different longstanding mysteries. One, is that Saturn’s present-day tilt, and two, the age of the planet’s rings, both of which were estimated to be around 100 million years old, which is much younger than the planet’s age.

According to professor of planetary sciences at MIT and lead author of the new study, Jack Wisdom, “just like a butterfly’s chrysalis, this satellite was long dormant and suddenly became active, and the rings emerged.”

The study’s co-authors include Rosa Dbouk at MIT, William Hubbard at the University of Arizona, Burkhard Militzer of the University of California at Berkeley, Richard French of Wellesley College, and Francis Nimmo and Brynna Downey of the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Progress During the Early 2000s

As the scientists continued to study Saturn, in the early 2000s, they put an idea forward that Saturn’s tilted axis was actually due to the planet ‘being trapped in a resonance, or gravitational association, with Neptune.’ However, a new twist on the issue came up after observations that were taken from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft between 2004 to 2017 came up. What researchers found was that Saturn’s largest satellite, Titan, was actually migrating away from Saturn at a faster clip than expected – a rate of around 11 centimeters per year. Scientists believe that because of Titan’s quick migration, as well as its gravitational pull, the moon was more likely to be responsible for the tilting while keeping Saturn in resonance with Neptune.

Although this particular explanation depends on one major unknown factor, which is Saturn’s moment of inertia or the way its mass is distributed in the planet’s interior. The planet’s tile could behave differently than usually, all depending on whether the ‘matter is more concentrated at is core or toward the surface,’ they explain.

Wisdom says, “To make progress on the problem, we had to determine the moment of inertia of Saturn.”

A Lost Element

In this new study, Wisdom and his colleagues thought to pin down Saturn’s moment of inertia via some of the last few observations that were taken by the Cassini in what they refer to as the “Grand Finale” – the phase of the mission where the spacecraft ended up making a very close approach in order to ‘precisely map the gravitational field around the entire planet.’ The scientists explain that the gravitational field is used to figure out the distribution of the planet’s mass.

The research team modeled the interior of Saturn, and then identified a distribution of mass that matched that of the gravitational field which Cassini observed. Notably, what they found was that this newly identified moment of inertia found Saturn quite close to but outside the resonance with Neptune. While the planets may have formerly been in sync, they are no longer in sync.

Wisdom explains, “Then we went hunting for ways of getting Saturn out of Neptune’s resonance.”

To see if there were any natural instabilities among the satellites in existence influenced Saturn’s tilt, the research group carried out simulations to evolve the planet’s orbital dynamics and its moons backward in time. But their search came up empty.

As a result, the scientists reexamined the mathematical equations that describe a planet’s precession, which is actually ‘how a planet’s axis of rotation changes over time.’ As for one particular term in this equation, it has contributions from all the satellites. According to the team, the shared that ‘if one satellite was removed from this sum, it could affect the planet’s precession.’

But the question remains, how big would that satellite have to be, and what dynamics does it need to undergo to remove Saturn from Neptune’s resonance?

Wisdom and his colleagues ran some simulations to figure out the properties of a satellite, like its mass and orbital radius, as well as the orbital dynamics that are needed to knock Saturn out of the resonance.

In conclusion, they share that Saturn’s present tilt is the result of the resonance with Neptune, and as for the loss of its satellite, Chrysalis, which is around the size of Iapetus – which is Saturn’s third-largest moon – is what allowed it to escape the resonance.

It was sometime between 200 and 100 million years ago when Chrysalis entered a chaotic orbital zone, allowing it to experience a number of close encounters with Titan and Iapetus, which eventually came to close to Saturn. This was a grazing encounter that ended up ripping the satellite to bits, ‘leaving a small fraction to circle the planet as a debris-strewn ring.’

What they found was that the loss of Chrysalis explains Saturn’s precession, as well as its present-day tile, and the late formation of its rings.

Wisdom explained in an article in MIT News, “It’s a pretty good story, but like any other result, it will have to be examined by others. But it seems that this lost satellite was just a chrysalis, waiting to have its instability.”

What are your thoughts? Please comment below and share this news!

True Activist / Report a typo